The Global Fund spends its resources on a few key processes: purchasing commodities, distributing them, and supporting the services delivered at health facilities. As a funder and payer rather than an implementer, the Global Fund cannot control the efficiency of these processes, but it can influence them. Improving its tracking of costs and spending could lead to better decisions by recipients, and better oversight by the Fund and its partners.

Information on costs and spending helps decision-makers identify waste and understand which services provide more health for the money.

Information on costs and spending helps decision-makers identify waste and understand which drug manufacturers, health-care providers, or other actors provide the best results for the money. In some cases, the mere disclosure of average unit costs of a commodity can result in savings. Cost and spending data can also help governments track and streamline country-level program expenditures.

Some Progress; More to Do

The Global Fund and its partners are taking steps to better track costs and spending. Some steps have already improved efficiency. But opportunities remain to build on that progress and further support the creative efforts of recipients to improve efficiency in the Global Fund’s three core areas—commodities, supply chains, and service delivery.

Value for Money in Action: The average cost of bed nets purchased with Global Fund support fell more than 40% from 2009 to 2012.

Commodities

The Global Fund spends a great deal of resources on purchasing commodities such as bed nets, condoms, diagnostic tests, and medicines. Recipients record and track the prices paid for some medical commodities on a web-based system called the Price Quality Reporting (PQR), which is probably partially responsible for bringing prices down in recent years. For example, the average unit cost for long-lasting insecticide-treated bed nets purchased with Global Fund support decreased from US$5.10 in 2009 to US$3.03 in 2012. Another reason prices have fallen is voluntary pooled procurement, which brings grant recipients together to purchase commodities at a lower cost.

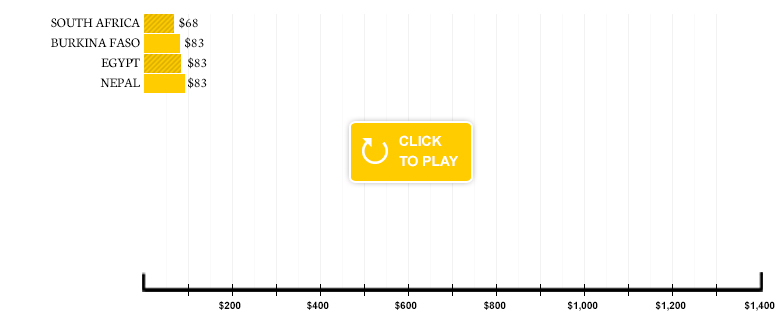

Some prices may be falling, but they still vary from one country to another. For example, South Africa paid $66.83 per person-year for Ritonavir 100mg (a second-line ARV) in November 2010. Less than a month later, the West Bank/Gaza paid $1,216.62 for the same commodity—almost 18 times more.

Variation in Reported Cost (USD) per Patient-Year for Ritonavir 100mg, September 2010-April 2013, As Reported by the Global Fund

The Global Fund also finances the purchase of nonmedical commodities such as vehicles, computers, and office supplies. These supplies are supposed to be tracked through the Enhanced Financial Reporting system, but various limitations of the tool have led to its disuse.

Supply Chains

Purchasing commodities is step one. Next, they have to get to health-care providers, but the way is not always smooth. Supply-chain costs and performance can be highly variable. According to one analysis, only 7 of 37 sub-Saharan African countries have an efficient supply chain for ordering and shipping contraceptives. Poor supply chains can leave health facilities out of stock of essential medicines; estimates suggest that the average availability of drugs at public health facilities in low- and middle-income countries is less than 25 percent. Stock-outs can have deadly consequences, like increased transmission of malaria and disruption of services for life-saving AIDS and TB drugs.

Efficient supply chains make sure life-saving commodities get to the right place at the right time for the right price.

Service Delivery

Cost variations don’t end with purchasing and supply chains. Cost variation is also evident for service delivery at health facilities, even within a single country. For example, data from a sample of 45 facilities in Zambia show that the annual costs of treatment for one person could vary from $1,020 to $411 depending on characteristics of the facility including service quality, environmental factors, and the scale of operations. But it remains unknown the extent to which these discrepancies may also be attributable to inefficiencies in service delivery.

Several global health funders are trying to better understand the sources of service-delivery cost variations, and their efforts show that reducing the variation could save a lot of money. A PEPFAR expenditure analysis, for instance, found that sharing the unit cost of commodities with facility managers and operational staff from ART facilities in Mozambique was associated with a 45 percent reduction in costs.

Services at one facility may be more expensive than at another for many valid reasons. A one-size-fits-all approach to controlling costs is therefore inappropriate and potentially harmful, but a more nuanced approach can help everyone involved better understand their cost structures and drivers and squeeze further efficiencies throughout implementation.

We have been interested in the products without keeping our eye on the ball -- on the ball of the processes, on the ball of distribution, on the ball of storage, and on the ball of use.-Martha Gyansa-Lutterodt, Director of Pharmaceutical Services, Ministry of Health, Ghana

Recommendations

There are many ways to track unit costs of products and services and use that information to improve value for money. Much of this work can be led at the country level by grant recipients and program administrators. The following recommendations provide broad guidance on the collection and uses of cost and expenditure data, while leaving space for the Global Fund and its partners to craft appropriate responses to the findings of these exercises.

Continue to Improve the Scope, Completeness, and Timeliness of Reporting to the PQR

The Global Fund’s PQR system provides the information needed to help drive down the costs of commonly funded health commodities. But the dataset remains incomplete. The Global Fund should include in PQR reporting all commodities supported by its grants. In the medium term, the Fund should extend PQR reporting to include the costs of supply chains and service delivery at the product’s ultimate point of use. The Global Fund should also consider expanding the PQR to include commonly purchased high-cost items, such as computers and vehicles.

Use Data on Supply Chain Costs and Outputs to Improve Efficiency

Comparing the unit costs of outputs can provide key information on performance at different stages in the supply chain, and inform changes to improve efficiency. For example, PEPFAR saved an estimated $38.9 million over four years through tweaks to its supply chain such as using more ground and sea routes rather than pricey air freight. This kind of cost analysis is common practice, but is still underutilized in Global Fund countries.

Identify Core Services for More Extensive Analysis and Use of Service Delivery Costs and Spending

The Global Fund should identify the most costly and most frequently used health interventions that would be good candidates for enhanced data collection, analysis, and use. The Global Fund already reports estimated service delivery costs for first- and second-line ARV therapy at the national program level. By building off this experience or by contracting out to a specialized organization, the Global Fund can expand this costing exercise to other services that it frequently funds, such as tuberculosis and malaria treatment.

Share Cost and Spending Data with Partners and the Public

The Global Fund currently participates in an information-sharing network with other global health funders, and has pledged to share financial and programmatic data with external stakeholders as a signatory to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI). Building on this commitment, the Global Fund and its partners should distribute relevant information from costing and commodity price tracking systems to build knowledge on the costs of program implementation, to reduce duplication, and to strengthen and standardize costing methods where feasible. Beyond sharing data, the Global Fund and its partners should create more open lines of communication to identify gaps in the research and agree on an efficient division of labor to evaluate different aspects of their shared agenda. The Global Fund has already begun studies with PEPFAR—such collaboration, if found to be effective, should be continued and expanded.

Develop a Strategy to Use Cost and Expenditure Data in the New Funding Model

The Global Fund’s new funding model provides an opportunity to better integrate supply chain and service delivery data with cost and expenditure data. The strategy can clarify which data are required by whom to drive real-time improvement in the performance of programs. The Global Fund should also encourage countries to include in their proposals unit costs from previous grants to inform future budgets.